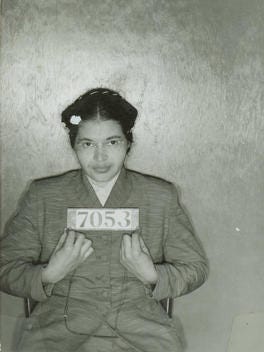

The 1955 arrest of what woman led to a boycott of the Montgomery bus system

In honour of Rosa Parks' birthday on Feb. 4, we're reposting this story almost her fateful decision that changed Montgomery, the state of Alabama, the United States and the globe.

When Rosa Parks refused on the afternoon of Dec. ane, 1955, to give up her double-decker seat so that a white human being could sit, it is unlikely that she fully realized the forces she had gear up into motion and the controversy that would soon swirl around her.

Other black women had similarly refused to give up their seats on public buses and had even been arrested, including two young women earlier that same yr in Montgomery. But this time the outcome was different.

Dissimilar those earlier incidents, Rosa Parks "courageous refusal to bow to an unfair police sparked a crucial chapter in the Ceremonious Rights Movement in the United States, the Montgomery Bus Boycott."

"I didn't get on the bus with the intention of being arrested," she oft said later. "I got on the passenger vehicle with the intention of going dwelling house."

Pressures had been building in Montgomery for some time to deal with public transportation practices that treated blacks as 2d-form citizens. Those pressures were increased when a 15-yr-old daughter, Claudette Colvin, was arrested on March 2, 1955, for refusing to surrender her seat to a white person.

Colvin did not violate the city bus policy past not relinquishing her seat. She was non sitting in the front seats reserved for whites, and there was no other identify for her to sit. Even under the double standards of the bus seating policy at the time, blacks sitting behind the white reserved section in a omnibus were but required to give up their seats to whites if there was another seat available for them. But despite the apparent legality of her refusal to give up her seat, Colvin was nevertheless convicted.

Some of the metropolis'due south blackness leaders thought that they had missed an opportunity for more than serious activeness post-obit the Colvin arrest. So when Parks was arrested a few months later, the stage was already set for a boycott. Responding to the arrest of Parks was E.D. Nixon, a Pullman train porter who led the state chapter of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. Nixon had worked for better conditions for blacks for decades. He organized the Montgomery Voters League in 1943 and served every bit president of both the state and local chapters of the NAACP. With the assistance of white attorney Clifford Durr, Nixon bailed Mrs. Parks out of jail on the evening of Dec. 1. He and so persuaded her to allow her example to be used to challenge the cityÍs bus segregation policy. Many of the almost pregnant decisions influencing not merely the cold-shoulder, but also the Civil Rights Motility of the 1950s and 1960s, were made behind the scenes between the time of Parks' arrest late that Thursday and the historic flood of events the post-obit Monday.

After leaving the Parks domicile, Nixon talked on the phone with Alabama State College professor Jo Ann Robinson, who had conferred with attorney Fred Grey. They agreed that a long-term legal challenge of coach segregation should be underscored past a ane-twenty-four hour period boycott of the omnibus system. That evening Nixon and Robinson went about setting the boycott into move.

Nixon spent the tardily evening talking on the telephone and drawing upwardly a list of names of people whose support he felt was essential, including many of the more prominent black leaders of Montgomery.

Robinson, who was president of the Women's Political Council, a group of black women who lobbied the city and state on black issues, had been pushing for a jitney boycott for months. She saw an opportunity and took it. In her memoir, Robinson recalls some notes she made that evening: "The Women'southward Political Council volition not wait for Mrs. Parks'south consent to call for a boycott of metropolis buses. On Friday, Dec 2, 1955, the women of Montgomery will telephone call for a boycott to accept place on Mon, December 5." By around midnight, Robinson had written a flier calling for a boycott. She called a colleague at Alabama Land, who agreed to let her use a mimeograph automobile to print copies of the flier. With his help and the aid of two of her students, Robinson spent the early on morning time hours of Dec. 2 duplicating, cut and bundling the flier. They finished about four a.g., only about 10 hours later on the abort of Parks.

The flier read: "Some other Negro woman has been arrested and thrown in jail considering she refused to get up out of her seat on the bus for a white person to sit down downwards. It is the second time since the Claudette Colvin case that a Negro woman has been arrested for the same thing. This has to be stopped. Negroes have rights, too, for if Negroes did non ride the buses, they could not operate. 3-fourths of the riders are Negroes, yet we are arrested, or take to stand up over empty seats. If we practice not exercise something to stop these arrests, they will proceed. The adjacent time information technology may exist y'all, or your daughter, or mother. This adult female'southward example will come up on Monday. Nosotros are, therefore, request every Negro to stay off the buses Monday in protest of the arrest and trial. Don't ride the buses to piece of work, to town, to school, or anywhere on Monday. You tin afford to stay out of school for one 24-hour interval if yous have no other way to go except by omnibus. You tin too beget to stay out of town for ane day. If you work, take a cab, or walk. But delight, children and grown-ups, don't ride the bus at all on Monday. Delight stay off all buses Monday."

After her class Friday morning, Robinson called other members of the WPC to discuss distributing the flier. During the remainder of the day, bundles of leaflets were dropped off at black schools and businesses where blacks were likely to congregate.

Robinson and the WPC essentially took the determination about a boycott of the Montgomery bus system out of the hands of more conservative black leaders and left them no existent choice only to go forth with at least a one-day version of it.

Nixon spent that Friday morning calling to recruit those whose leadership he felt was essential. Amid them were the Rev. Ralph Abernathy and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. Rex, later on some hesitation, agreed to participate. As Nixon telephoned leaders, they in turn contacted others. A meeting was arranged for King'south church.

At that coming together, attended by near 50 people, the decision was made that a mass meeting to which all blacks in the metropolis would be invited would be held Mon night, Dec. 5, at Holt Street Baptist Church. Rex led a committee which added language about the mass meeting to the WPC flier and distributed another 7,000 copies that Saturday.

Monday, Dec. v, was an historic day. The boycott began, Rosa Parks was tried in city court and convicted, the initial meeting of what would become the Montgomery Improvement Association was held, and a mass coming together of black citizens fabricated history.

That Monday dawned cold but clear. Morning buses that normally would be crowded with blacks heading to work throughout the city were essentially empty.

Instead, many blacks gathered near the motorbus stops, waiting for rides. Interestingly, many of those rides came from whites whose primary involvement was getting their domestic employees to their homes or other workers to their places of business. Other blacks rode Negro taxis, with many drivers giving reduced fares that day. Thousands more walked to work and school. Participation far exceeded the best hopes of the boycott leaders.

Meanwhile that Monday, Rosa Parks was appearing in courtroom.

Like Claudette Colvin before her, Parks had non technically violated the passenger vehicle ordinance. Despite that fact, and the ramble issues raised past her chaser, Fred Gray, the city guess institute Parks guilty and fined her $ten plus $four in court costs. That determination would further stir the black community to activeness.

In midafternoon, xvi to 18 people gathered in the pastor's written report of the Mt. Zion AME Zion Church building to discuss strategies. These advertising hoc leaders of the movement agreed that a new organization was needed to lead the boycott try if it was to continue. The Rev. Ralph Abernathy suggested the proper noun "Montgomery Improvement Association," and information technology was adopted. Discussions of who would exist the best spokesman for the boycott effort had been part of the give and take throughout the weekend. Gray and Robinson recalled in their books on the boycott that they had discussed Robinson's minister, Martin Luther King Jr., with East.D. Nixon. Knowing that there already existed cliques in the black community and resentments over roles, there was a consensus that a new face was necessary to lead the MIA. That person turned out to be King. In afterwards years, various participants claimed to take been the person who put King's proper name forrad. Attorney Greyness reported that blacks started gathering as early every bit 3 p.g. for the mass meeting at Holt Street Baptist Church scheduled for 7 p.1000., where Male monarch was set to requite the opening address, his first as a civil rights leader.

Grayness later wrote that he had prepared two resolutions for that evening: One in case that day's boycott had failed, which called for negotiations with city officials to resolve differences, and another in case the boycott was a success, calling for all black citizens of Montgomery to not ride the buses until they were desegregated. The first resolution was not needed.

King's speech stirred the chiliad or more than people packed into every corner of the church. He urged them to apply Christian love as a tool to protect their rights: "But I want to tell you this evening that it is not enough for the states to talk near love. Love is one of the pivotal points of the Christian faith. In that location is another side called justice. And justice is really love in calculation. Justice is love correcting that which revolts against love." Buoyed past the success of that day's boycott and past King'due south rousing spoken language, the audience rose and cheered when asked to support a resolution to proceed the boycott.

The historic Montgomery Bus Boycott had begun. It would last for 381 days, a bridge during which life for nearly every black Montgomerian changed dramatically.

Researchers estimate that some 17,000 blacks took function in the boycott initially, although the numbers quickly grew because of activeness by the motorbus system itself. Before long after the cold-shoulder concluded, King claimed that 42,000 blacks took function.

A few days later on the boycott began, charabanc officials asked the City Committee for permission to shut routes to many of the primary blackness communities, arguing that the boycott had fabricated service to those areas no longer financially bonny. So in those parts of town, even the handful of blacks who might accept wanted to employ the buses could not practice so.

For the beginning few days of the cold-shoulder black taxi companies helped transport former autobus riders. Boycott leaders persuaded most of these companies to charge only 10 cents per ride during the hours almost blacks were going to and coming from work. But a few days into the boycott, city officials started to enforce a previously ignored city ordinance that set minimum fares at 45 cents. That priced taxi rides on a daily ground out of the achieve of many working-class blacks. Also, at the urging of blackness churches, blacks who owned cars gave rides to friends and neighbors.

Early in the boycott many white citizens also helped provide transportation to and from work for their black employees. Merely over time, the number of whites providing transportation dwindled nether pressure from others in the white customs.

Cold-shoulder leaders quickly realized that their plans for a more than organized alternative transportation system would accept to exist put into high gear if the boycott were to succeed long term.

Churches bought cars and station wagons specifically for the transportation system. Pick-up and delivery points were designated around the city and routes established. The city police harassed the organization past enforcing laws against crowding and a variety of minor traffic violations, but information technology succeeded anyway.

The car pool organization soon developed into an efficient, cost-effective ways of transportation.

As the boycott wore on, intimidation tactics took various forms. The most sweeping official action designed to deter boycott leaders came in February 1956, when the Montgomery g jury indicted 89 boycott leaders — including Rex, Parks, Abernathy and most of the other participating black ministers. The charges were based on a 1921 country statute that barred boycotts without "just crusade." Those indicted were arrested over the next few days, booked and released on bond. But every bit official tactics failed to discourage the boycott, unofficial intimidation soon took a more dangerous turn. In January, the parsonage in which King and his family lived was bombed. Coretta Scott King and the Kings' two-year-onetime girl narrowly escaped injury. Rex stood on his damaged porch and persuaded an angry crowd of blacks, some of them armed, not to answer with violence. The side by side night, E.D. Nixon'southward home was also bombed.

In August, the home of white Lutheran minister Robert Graetz too was bombed. Graetz, whose church was all-black, was probably targeted considering he was the only white member of the board of the Montgomery Improvement Association. His home was later bombed once again.

Even past the end of the boycott, the violence continued. In addition to bombings, King'southward home was shot into. After the cold-shoulder came to a shut, snipers shot into buses in black communities, at one point hitting a young black adult female, Rosa Jordan, in the legs. Her injuries were not life-threatening.

The worst single nighttime of violence occurred on Jan. 10, 1957, a few weeks after the end of the boycott and segregated seating on buses. Four black churches and 2 homes were bombed, including the Rev. Ralph Abernathy'south church and parsonage.

"Dr. King used to talk most the reality that some of us were going to dice and that if whatsoever of us were afraid to die we really shouldn't exist at that place," Graetz said. The intimidation tactics failed to significantly deter any black boycotters. Instead, for the most part, they spurred black Montgomerians to greater efforts.

In an analysis of the Montgomery Autobus Cold-shoulder printed in the periodical "Liberation" in 1957, King wrote: "Because the mayor and urban center authorities cannot admit to themselves that we (black Montgomerians) have changed, every motility they have made has inadvertently increased the protestation and united the Negro community." Just days after the offset of the bus cold-shoulder, boycott leaders began discussing the demand for a federal lawsuit to claiming city and state bus segregation laws. On Jan. xxx, 1956, (the day the Rev. Martin Luther Rex Jr.'s home was bombed in the early morning hours) the executive board of the MIA decided to sue in federal court. Two days later, attorneys Fred Gray and Charles Langford filed a lawsuit on behalf of four female plaintiffs. Information technology was known as Browder v. Gayle. (Browder was a Montgomery housewife; Gayle the mayor of Montgomery.)

Gray recalls in his memoir, "Bus Ride to Justice," that discussions with MIA leaders about a federal lawsuit began nearly two weeks after the first of the boycott. Gray chop-chop began research for the lawsuit, consulting several sympathetic attorneys, including his friend and mentor Clifford Durr. He also consulted with NAACP legal counsels Robert Carter and Thurgood Marshall, who would subsequently go U.Southward. solicitor general and a U.S. Supreme Court justice.

Grayness after wrote that he felt a lawsuit was crucial to bolstering the commitment of those who were conducting the boycott, giving them promise that they could prevail even if metropolis officials stood firm in the face of the boycott itself. Time and events proved Gray's thinking was correct.

It is ironic that in the early on days of the cold-shoulder, when MIA officials were still negotiating with officials of the city and the bus line, their demands stopped far short of ending segregation on city buses. Instead, those negotiations focused on ending the practices of forcing blacks to stand and so that whites could sit, such equally in the case of Rosa Parks, or of forcing blacks to leave seats in the front end of the black section of a double-decker so that whites could fill them if the white section was full. The boycott leadership likewise sought the hiring of some black bus drivers and more courteous treatment of blackness riders past bus drivers.

If city officials had given in to these modest demands, they would take batty the boycott and quite likely take caused the focus of the Civil Rights Motility to have shifted to some metropolis other than Montgomery. Indeed, business interests in Montgomery, supported by the Montgomery Advertiser's editorial page, supported some class of compromise, every bit did the majority of the leadership of the MIA.

But urban center officials, pressured past the militant and racist White Citizens Councils, refused to budge. In the early weeks of the boycott, then-Mayor W.A. Gayle declared: "Nosotros are going to hold our stand. We are not going to be a office of any program that will get Negroes to ride the buses once again at the price of the destruction of our heritage and way of life." The intransigence on the function of metropolis officials prompted MIA leaders to widen their demands when they went to federal court.

"We ended that if we were e'er going to get anywhere, we would have to get to the federal court," Greyness said. "So once we got to that point, we didn't ask the federal courtroom for this (original) point we (had) approached the city with. We filed to end segregation." The plaintiffs in the case were Aurelia Browder, a housewife; Mrs. Susie McDonald, a black woman in her seventies; Claudette Colvin, the xv-year-old arrested in March 1955 for refusing to give up her coach seat; and Mary Louise Smith, an 18-year-old arrested under similar circumstances in Oct 1955. The four women shared the distinction of being black women who had been treated unfairly on city buses because of their race.

The Rosa Parks instance was not used as the basis for the federal lawsuit for several reasons. Every bit a criminal statute, information technology would have to wend its way through the state criminal appeals process before a federal entreatment could exist filed. Metropolis and country officials could have delayed a concluding rendering for years. In addition, information technology is possible that the only effect would take been that the confidence of Parks would be vacated, with no lasting affect on bus segregation.

A hearing on Browder v. Gayle was held in Montgomery on May xi, 1956. The plaintiffs outlined their harsh handling on metropolis buses earlier a panel of iii federal judges: Appeals Court Guess Richard T. Rives, Montgomery Commune Estimate Frank M. Johnson Jr., and Birmingham District Judge Seybourn H. Lynne.

The attorneys for the black plaintiffs argued that the 1954 Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Educational activity of Topeka, Kansas applied not only to public educational activity, but to public transportation as well.

On June v, the special panel ruled ii to one in favor of the black plaintiffs. Rives' majority opinion in which Johnson concurred held that the 1954 Dark-brown ruling, which had overturned the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson "split up merely equal" doctrine, applied not only to public schools merely to other forms of legalized segregation, including public transportation. The three-approximate console delayed enforcement of its ruling until the urban center had exhausted its appeals. Considering of that delay, the MIA leadership felt the boycott should go on.

Every bit the federal case wound on, MIA attorneys had their hands total staving off attempts in state courts by the urban center to end the boycott, including the prosecution of boycott leaders for violating the country's anti-cold-shoulder police and an effort to enjoin the operation of the MIA's car pool. On Nov. 13, the day the urban center got a country court injunction to shut down the car pool, the U.South. Supreme Court ruled in favor of the plaintiffs in the Browder v. Gayle case. As soon every bit new mass meetings could be arranged, several thousands blacks voted to terminate the boycott when the loftier court'southward enforcement social club was served. That occurred on Dec. 20, 1956, and black Montgomerians — led by King — returned to the city buses the next solar day. The 381-twenty-four hour period cold-shoulder of Montgomery buses finally had ended. Not simply could the black residents of Montgomery now ride city buses every bit equals, thanks to their efforts so could many other black citizens throughout the nation.

fishbournemoothoung.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.montgomeryadvertiser.com/story/news/2017/12/01/rosa-parks-arrest-day-1955-sparked-montgomery-bus-boycott-and-changed-world/912612001/

0 Response to "The 1955 arrest of what woman led to a boycott of the Montgomery bus system"

Post a Comment